Garter Snakes in Africa?

Why are there garter snakes in Africa? Are they related to the garter snakes in North America? The answer to these questions and more are addressed in this blog!

GARTER SNAKESSCIENTIFIC

Grace Zumbrun

11/15/20259 min read

I thought all garter snake species were located in North America, but then my husband decided to throw me for a loop. THERE ARE GARTER SNAKES IN AFRICA?! But, in typical Harrison fashion, he left out some pretty important information on purpose…. like how they actually ARE NOT true garter snakes, but they are apparently pretty similar, but I will let you be the judge of that!

Wait… African “Garter Snakes”?

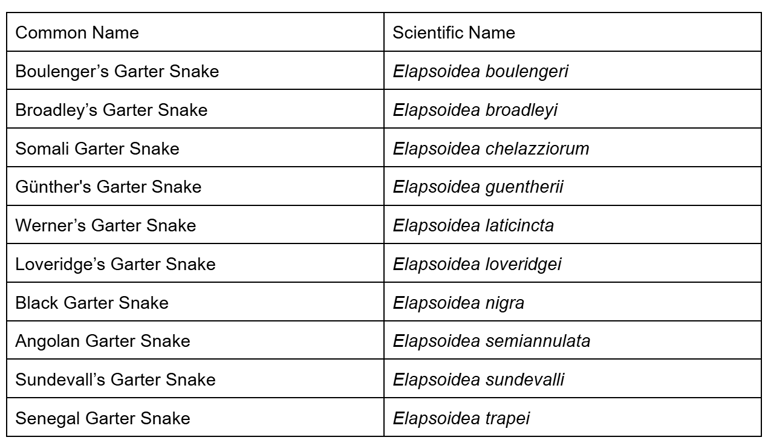

These so-called “garter snakes” belong to the genus Elapsoidea which, if you recall, is not Thamnophis, the genus that North American garter snakes belong to. There are 10 recognized in Elapsoidea. Of course, there are various subspecies, but I’m not getting into that today. See the table below for their common and scientific names

Taxonomy Time! (And Some History)

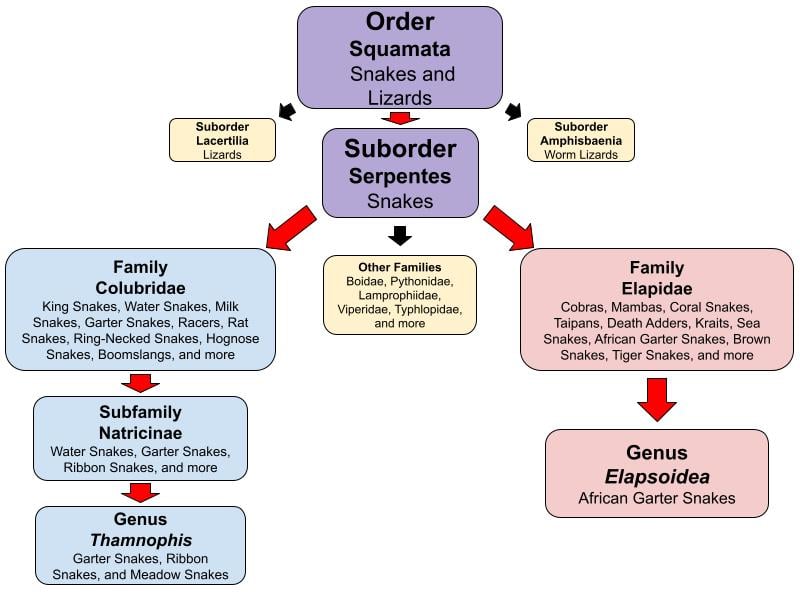

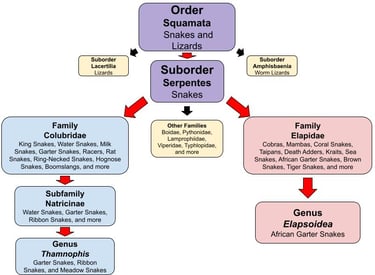

Thamnophis and Elapsoidea genera do not share the same family or subfamily!

Their lineage only converges at the suborder Serpentes, just like all other snakes! So, genetically, they are very different from each other.

The Elapsoidea genus was established in 1866 by Albert Günther. The first species that falls into the genus is Sundevall’s Garter Snake and it was described by Sir Andrew Smith in 1848. Thamnophis was established earlier in 1843 by Leopold Fitzinger, but the first species was described way back in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus. That species was most likely the Eastern garter snake based on descriptions of the specimen and the locality from which it came from, but it was definitely a subspecies of the common garter snake (Linnaeus wasn’t even in the US!). So with that said, the North American garter snakes came first by a long shot for both genus establishment and first species described. It is likely that the term “African garter snake” likely arose in the early 1900s because Elapsoidea look somewhat like Thamnophis.

A Brief Nerd-Out on the Taxonomists

All the scientists mentioned above lived around the same era and, directly or indirectly, worked off each other’s systems. All three of the other men cataloged their species by following the binomial nomenclature that was established by Carl Linnaeus. Another name for Linnaeus is the “Father of Modern Taxonomy”! Binomial nomenclature is the method of naming a species with two-part names to help avoid any confusion by the use of common names. Fitzinger helped to reorganize genera Smith and others first described. Günther evaluated, accepted, or corrected systems created by Fitzinger relating to classification and he looked over and reclassified many of Smith's African specimens. You don’t need to know the messy details, but essentially, they all built on one another’s work, and that collaboration helped shape the garter snake classifications we use today.

Differences

1. Scales & Habitat

Elapsoidea → Smooth scales, ideal for burrowing. Smooth scales reduce friction underground (think of Kenyan Sand Boas, their scales feel almost soft!). If they had keeled scales, they’d snag on debris.

Thamnophis → Keeled scales, better for gripping slippery surfaces and swimming. Keeled scales also make them appear duller, offering better camouflage.

2. Patterning

Both have patterns, but for different environments:

North American garter snakes → Longitudinal stripes to blend into vertical grasses. The continuous stripes make it hard for predators to track where the snake begins and ends when it moves.

African garter snakes → Bands or rings, which offer camouflage when they stay still. Their rings resemble coral snake patterns, leading to both Batesian and Müllerian mimicry:

3. Reproduction

Elapsoidea → Oviparous (egg-laying), usually underground

Thamnophis → Viviparous (live-bearing)

4. Defensive Behavior

Elapsoidea → Prefer hiding underground. Will bite defensively.

Thamnophis → Prefer fleeing to water/vegetation. If grabbed, they musk (a foul-smelling defensive secretion). They also bluff strike and flatten their heads to appear larger.

5. Activity Patterns

Elapsoidea → Primarily nocturnal

Thamnophis → Primarily diurnal, though some southern species become crepuscular in hot climates

6. Venom & Fangs

This is a big one!

North American Garter Snakes

Rear-fanged, their venom is delivered by teeth located in the back of their mouth

Possess a Duvernoy’s gland, a rudimentary version that isn’t as developed as a true venom gland

Mild venom used for immobilizing prey, with no medical significance to humans

Venom also contains digestive enzymes that start to break down their food before it reaches the stomach allowing them to digest faster

African Garter Snakes

Front-fanged, part of the Elapidae family (cobras, kraits, mambas)

Have a true venom gland

Venom is medically mild compared to other elapids but still stronger than Thamnophis venom (Africans’ venom also contains digestive enzymes, but it is not the main benefit of their venom

Interesting case study:

A well-documented case of a man getting bit by Sundevall’s Garter Snake happened in 1980. Initially, the man had pain and slight swelling at the location of the bite, but then experienced distorted vision, loss of balance, nausea and drooping eyelids. Overnight, the symptoms peaked and then began to go away without antivenom. The only care he received was supportive (think fluids, pain medicine, etc that treat the symptoms, but not the cause) and he was able to return to work 2 days after the initial bite.

Antivenom exists for related species but is not typically used because the bites aren’t severe enough to justify the risk. Both genera have no recorded fatalities.

Poisonous North American Garter Snakes?

Some Thamnophis species become poisonous (not venomous) after eating toxic newts. They store newt toxins in their liver and skin, making predators sick or worse. African garter snakes do not do this.

Similarities Between the Two

1. Size & Build

Both are typically slender-bodied active hunters. African species tend to be slightly shorter and stockier, likely due to fossorial lifestyles.

2. Diet

Both genera are generalist predators, opportunistic eaters targeting amphibians, lizards, and small mammals.

3. Ecological Role

Both are mid-level predators: small enough to avoid many predators, large enough to hunt a variety of prey.

4. Camouflage Purpose

While their patterns differ, the function is the same: confusing and avoiding predators. Whether stripes or rings, both break up their outlines and help them disappear into their environments.

So… Are They More Similar or Different?

With all of this in mind, what do you think? Personally, I think they’re far more different than similar, and it’s wild that both groups ended up being called “garter snakes.”

Final note: Make sure to double-check that the garter snake that you are buying at a show is a friendly, HARMLESS, North American Garter, and not a potentially dangerous nope rope!

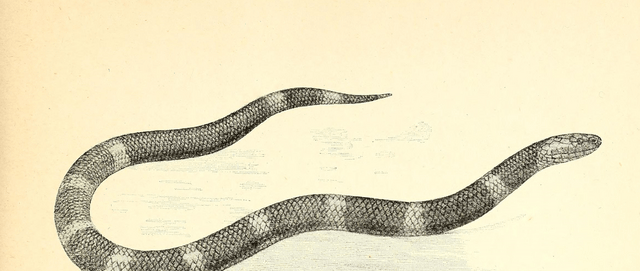

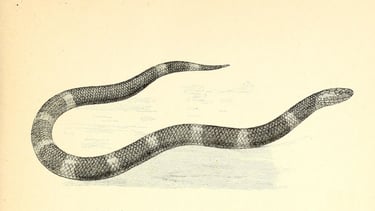

Sundevall's Garter Snake

Eastern Garter Snake

From left to right: Albert Günther, Carl Linnaeus, Sir Andrew Smith, Leopold Fitzinger

Smooth Scales

Keeled Scales

Batesian: harmless species mimicking harmful ones (Common example: viceroy butterflies and monarch butterflies)

Müllerian: harmful species sharing patterns for mutual protection (Common example: All poison dart frogs being brightly colored)

African garter snakes, as far as we know, do not musk.

Do you know which is which?

Boulenger's Garter Snake

Aquatic Garter Snake

I thought all garter snake species were located in North America, but then my husband decided to throw me for a loop. THERE ARE GARTER SNAKES IN AFRICA?! But, in typical Harrison fashion, he left out some pretty important information on purpose…. like how they actually ARE NOT true garter snakes, but they are apparently pretty similar, but I will let you be the judge of that!

Wait… African “Garter Snakes”?

These so-called “garter snakes” belong to the genus Elapsoidea which, if you recall, is not Thamnophis, the genus that North American garter snakes belong to. There are 10 recognized in Elapsoidea. Of course, there are various subspecies, but I’m not getting into that today. See the table below for their common and scientific names

Taxonomy Time! (And Some History)

Thamnophis and Elapsoidea genera do not share the same family or subfamily!

Their lineage only converges at the suborder Serpentes, just like all other snakes! So, genetically, they are very different from each other.

The Elapsoidea genus was established in 1866 by Albert Günther. The first species that falls into the genus is Sundevall’s Garter Snake and it was described by Sir Andrew Smith in 1848. Thamnophis was established earlier in 1843 by Leopold Fitzinger, but the first species was described way back in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus. That species was most likely the Eastern garter snake based on descriptions of the specimen and the locality from which it came from, but it was definitely a subspecies of the common garter snake (Linnaeus wasn’t even in the US!). So with that said, the North American garter snakes came first by a long shot for both genus establishment and first species described. It is likely that the term “African garter snake” likely arose in the early 1900s because Elapsoidea look somewhat like Thamnophis.

A Brief Nerd-Out on the Taxonomists

All the scientists mentioned above lived around the same era and, directly or indirectly, worked off each other’s systems. All three of the other men cataloged their species by following the binomial nomenclature that was established by Carl Linnaeus. Another name for Linnaeus is the “Father of Modern Taxonomy”! Binomial nomenclature is the method of naming a species with two-part names to help avoid any confusion by the use of common names. Fitzinger helped to reorganize genera Smith and others first described. Günther evaluated, accepted, or corrected systems created by Fitzinger relating to classification and he looked over and reclassified many of Smith's African specimens. You don’t need to know the messy details, but essentially, they all built on one another’s work, and that collaboration helped shape the garter snake classifications we use today.

Differences

1. Scales & Habitat

Elapsoidea → Smooth scales, ideal for burrowing. Smooth scales reduce friction underground (think of Kenyan Sand Boas, their scales feel almost soft!). If they had keeled scales, they’d snag on debris.

Thamnophis → Keeled scales, better for gripping slippery surfaces and swimming. Keeled scales also make them appear duller, offering better camouflage.

2. Patterning

Both have patterns, but for different environments:

North American garter snakes → Longitudinal stripes to blend into vertical grasses. The continuous stripes make it hard for predators to track where the snake begins and ends when it moves.

African garter snakes → Bands or rings, which offer camouflage when they stay still. Their rings resemble coral snake patterns, leading to both Batesian and Müllerian mimicry:

3. Reproduction

Elapsoidea → Oviparous (egg-laying), usually underground

Thamnophis → Viviparous (live-bearing)

4. Defensive Behavior

Elapsoidea → Prefer hiding underground. Will bite defensively.

Thamnophis → Prefer fleeing to water/vegetation. If grabbed, they musk (a foul-smelling defensive secretion). They also bluff strike and flatten their heads to appear larger.

5. Activity Patterns

Elapsoidea → Primarily nocturnal

Thamnophis → Primarily diurnal, though some southern species become crepuscular in hot climates

6. Venom & Fangs

This is a big one!

North American Garter Snakes

Rear-fanged, their venom is delivered by teeth located in the back of their mouth

Possess a Duvernoy’s gland, a rudimentary version that isn’t as developed as a true venom gland

Mild venom used for immobilizing prey, with no medical significance to humans

Venom also contains digestive enzymes that start to break down their food before it reaches the stomach allowing them to digest faster

African Garter Snakes

Front-fanged, part of the Elapidae family (cobras, kraits, mambas)

Have a true venom gland

Venom is medically mild compared to other elapids but still stronger than Thamnophis venom (Africans’ venom also contains digestive enzymes, but it is not the main benefit of their venom

Interesting case study:

A well-documented case of a man getting bit by Sundevall’s Garter Snake happened in 1980. Initially, the man had pain and slight swelling at the location of the bite, but then experienced distorted vision, loss of balance, nausea and drooping eyelids. Overnight, the symptoms peaked and then began to go away without antivenom. The only care he received was supportive (think fluids, pain medicine, etc that treat the symptoms, but not the cause) and he was able to return to work 2 days after the initial bite.

Antivenom exists for related species but is not typically used because the bites aren’t severe enough to justify the risk. Both genera have no recorded fatalities.

Poisonous North American Garter Snakes?

Some Thamnophis species become poisonous (not venomous) after eating toxic newts. They store newt toxins in their liver and skin, making predators sick or worse. African garter snakes do not do this.

Similarities Between the Two

1. Size & Build

Both are typically slender-bodied active hunters. African species tend to be slightly shorter and stockier, likely due to fossorial lifestyles.

2. Diet

Both genera are generalist predators, opportunistic eaters targeting amphibians, lizards, and small mammals.

3. Ecological Role

Both are mid-level predators: small enough to avoid many predators, large enough to hunt a variety of prey.

4. Camouflage Purpose

While their patterns differ, the function is the same: confusing and avoiding predators. Whether stripes or rings, both break up their outlines and help them disappear into their environments.

So… Are They More Similar or Different?

With all of this in mind, what do you think? Personally, I think they’re far more different than similar, and it’s wild that both groups ended up being called “garter snakes.”

Final note: Make sure to double-check that the garter snake that you are buying at a show is a friendly, HARMLESS, North American Garter, and not a potentially dangerous nope rope!